The heart of Rotary is the service club and the community in which it exists. People join first and foremost because they want to give back to their community. Finding fellowship and honing leadership skills are pleasant extras.

As Rotary grew and matured into an International organisation, it saw the need to give service beyond the local community and with the formation of a foundation created a means by which our motto “service above self” could broaden the concept of community to include the World.

This concept found its greatest expression in 1985 when Rotary decided to rid the world of Polio. It was a task of audacious magnitude and has forever changed Rotary.

We not only learned that we could do good in our community but throughout the entire World. Although we can take pride in this achievement, we should not forget that we also set in motion a new tension, between doing good locally and internationally.

With the creation of a new 21st Century funding model, many Rotarians are feeling this tension more than ever. Some feel that our leader's emphasis on international service takes precedence over local community needs.

The concept of Global grants and District Designated Grants (DDGs) make sense in theory; however, in reality, they make no allowance for the possibility that the home community may have needs as great or greater than areas of the world less developed than First World economies.

Global Grants are large, and Rotary wants according to a study mentioned at the 2018 Conference in Toronto to make them even larger, whereas DDGs are small, for example, a maximum of $2,500 in District 5550.

To make my point that even in a Country as wealthy as Canada there are pockets of need that mirror those found in the Third World, in fact, they may sadly, be worse.

I was inspired to think in this manner after reading Tanya Talaga’s book All Our Relations: Finding the Path Forward. Talaga chronicles the tragic reality of children feeling so hopeless they want to die, of kids perishing in clusters, forming suicide pacts, or becoming romanced by the notion of dying ― a phenomenon that experts call “suicidal ideation.” The problem is approaching the status of a global crisis, as evidenced by the high suicide rates among the Inuit of Greenland and Aboriginal youth in Australia. But nowhere else has youth suicide reached the epidemic proportions of the indigenous population of Northwestern Ontario where indigenous youth between ages ten to nineteen have five to six times the suicide rate than their peers in the rest of the country.

was inspired to think in this manner after reading Tanya Talaga’s book All Our Relations: Finding the Path Forward. Talaga chronicles the tragic reality of children feeling so hopeless they want to die, of kids perishing in clusters, forming suicide pacts, or becoming romanced by the notion of dying ― a phenomenon that experts call “suicidal ideation.” The problem is approaching the status of a global crisis, as evidenced by the high suicide rates among the Inuit of Greenland and Aboriginal youth in Australia. But nowhere else has youth suicide reached the epidemic proportions of the indigenous population of Northwestern Ontario where indigenous youth between ages ten to nineteen have five to six times the suicide rate than their peers in the rest of the country.

was inspired to think in this manner after reading Tanya Talaga’s book All Our Relations: Finding the Path Forward. Talaga chronicles the tragic reality of children feeling so hopeless they want to die, of kids perishing in clusters, forming suicide pacts, or becoming romanced by the notion of dying ― a phenomenon that experts call “suicidal ideation.” The problem is approaching the status of a global crisis, as evidenced by the high suicide rates among the Inuit of Greenland and Aboriginal youth in Australia. But nowhere else has youth suicide reached the epidemic proportions of the indigenous population of Northwestern Ontario where indigenous youth between ages ten to nineteen have five to six times the suicide rate than their peers in the rest of the country.

was inspired to think in this manner after reading Tanya Talaga’s book All Our Relations: Finding the Path Forward. Talaga chronicles the tragic reality of children feeling so hopeless they want to die, of kids perishing in clusters, forming suicide pacts, or becoming romanced by the notion of dying ― a phenomenon that experts call “suicidal ideation.” The problem is approaching the status of a global crisis, as evidenced by the high suicide rates among the Inuit of Greenland and Aboriginal youth in Australia. But nowhere else has youth suicide reached the epidemic proportions of the indigenous population of Northwestern Ontario where indigenous youth between ages ten to nineteen have five to six times the suicide rate than their peers in the rest of the country.This tragedy is a result of our colonial past where our white forefathers set up Apartheid-like reserves, broke or ignored treaties and began in the late 1800s a system of cultural genocide by establishing a residential school system followed by a child welfare system which morphed into the “sixties scoop”.

Talaga describes how the problem is so dire and so complex and the psychological and counselling services so minimal that hope almost vanishes from view as you read her story.

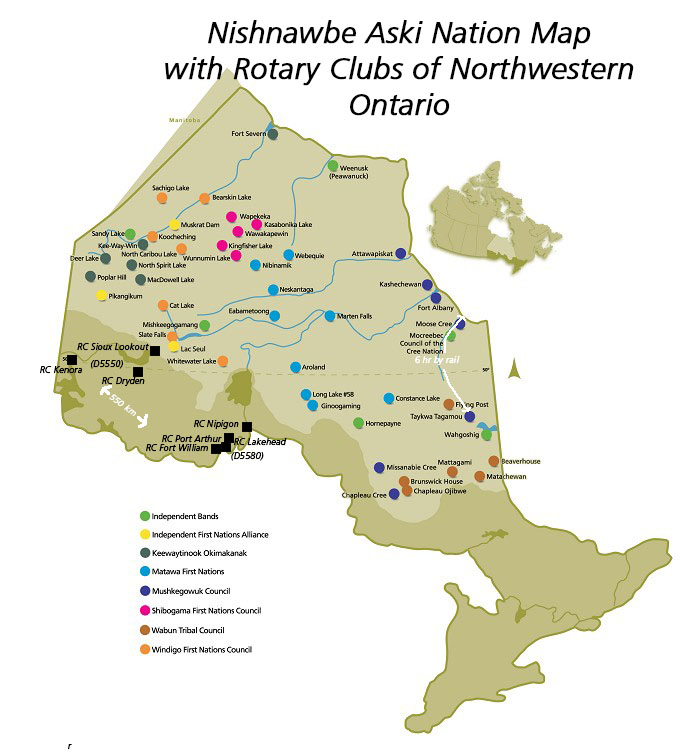

There are six Rotary Clubs spread over two District’s in the region; my club is one of them. It has one small literacy project underway at the $2,500 DDG level. It amounts to little more than a tiny pebble in a mountain of stones.

To fully appreciate the scope of the difficulty you have to understand the geography of this region. It is the size of France, or Texas or England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland and Erie combined. It has a population of maybe 190,000 of which over forty-thousand are indigenous living in the northern half in 49 communities few of which have land access to the south or each other except for six to eight weeks in the dead of winter when ice roads exist to bring in fuel and building materials.

The scope of the solution is huge and involves the need for millions of dollars. With courage and foresight, it is possible for a club working with other clubs, district’s and RI to plan a strategy with the Nishnawbe Aski Nation (NAN), and Provincial and Federal governments to develop long term and short term action plans to address the problems of youth suicide. As it stands now, there is no room for a Global Grant to assist local Rotarians to address such a monumental problem.

Another area looms large upon the horizon. There are currently 65,000,000 migrants escaping war, famine and other forms of violence. It doesn’t take a genius to realise that taking a “not-in-my-backyard” attitude grounded in fear, hatred and ignorance is tilling for disaster. Governments can not be expected to do everything. Cities size at all levels of national development has reached a magnitude never before seen. Rotary Clubs in cities and RI need to plan for the kinds of mega-projects which will need Global grants “locally” to be of use.

These are but two examples of where our current system of Global Grants is out of sync with reality and distort the heart of Rotary, the local community. We need to re-evaluate our criteria for the grant system to function equitably so the use of money from our World fund can address both international and local needs.

We want to be “People of Action” locally and internationally. We need to admit that sometimes the big actions are needed at home too.

If you like this article please click on the  icon to the bottom right.

icon to the bottom right.

icon to the bottom right.

icon to the bottom right. Be the first to start a conversation by posting a comment in the blog box below. Requires member login.